An Interview with ASOG director Seán Devlin

/On ancestral responsibility and how to pull off cinematic interventions as an independent filmmaker.

Vancouverites know of Seán Devlin as a stand-up comedian, or as the prankster that orchestrated a tactical media intervention against a former Canadian Prime Minister. The local artist is back in the limelight, this time as a filmmaker, with his genre-defying feature film, Asog.

I got a chance to review the film at the 42nd Vancouver International Film Festival. The storytelling I witnessed was bold and inspiring. Inspired by true events of disaster capitalism in the Philippines and tackling themes such as climate chaos, loss and grief, Asog makes audiences laugh and cry in equal measure. After winning a string of awards at film festivals across the world, the movie is now back for a limited run in select screens across the country. In Vancouver, a special screening on August 22, 2025 will feature an intro and Q&A with the filmmaker.

I was glad to have the opportunity to interview Seán Devlin about his artistic impulses and ethical notions that guide his creative ventures.

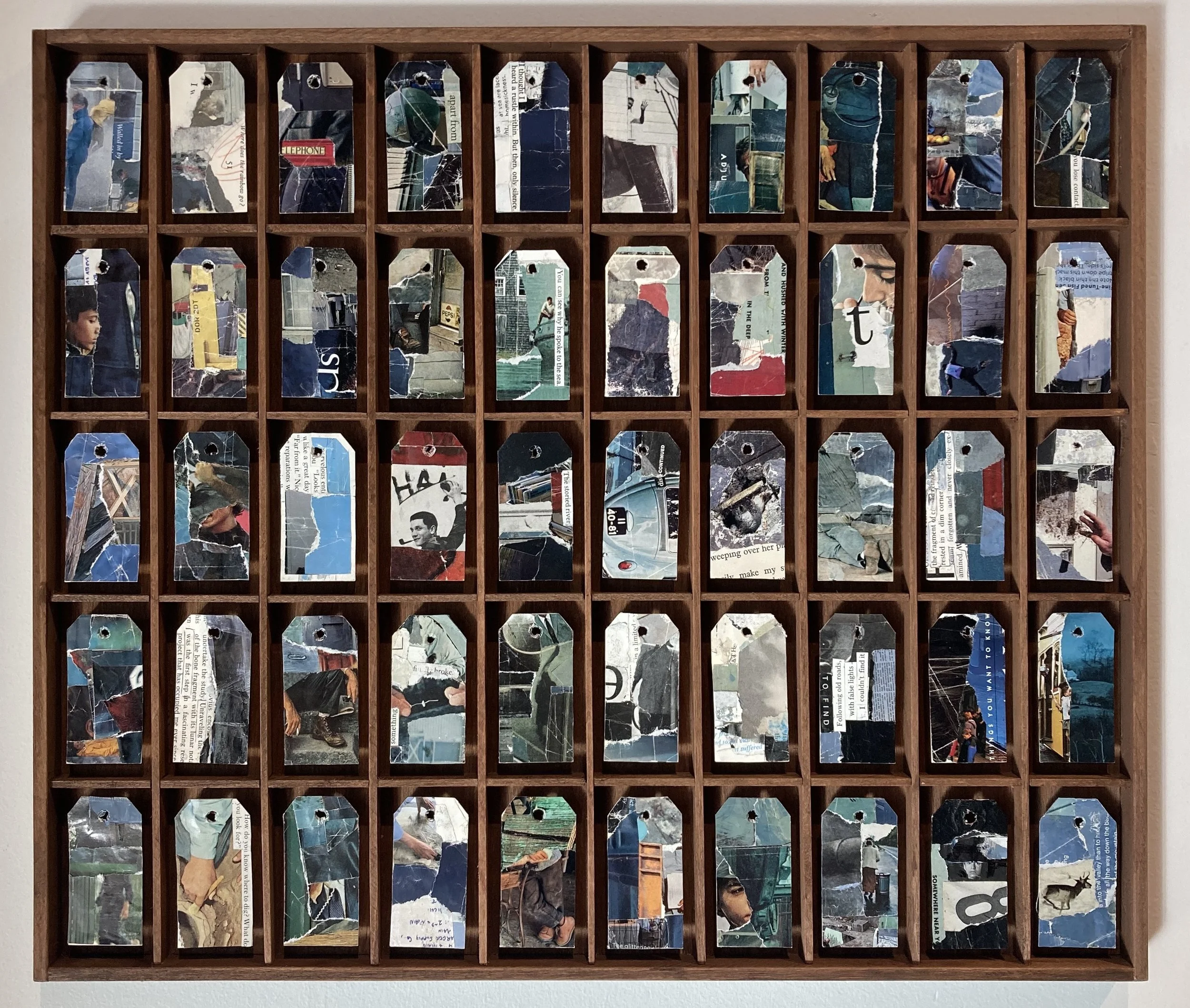

film still from asog by seán devlin

Shruthi Budnar: Most of your projects straddle that thin line between art and activism. Is it a tightrope walk?

Seán Devlin: When making something, I am most passionate about and drawn to art that isn't satisfied with simply commenting on the real world as an observer. Rather, I am interested in art that actually gets involved, that isn't on the sidelines. For me, that plays out in many different ways. A lot of my other work involves pranks. Asog doesn't involve pranks. But it has that similar quality where it is a piece of art that gets into the middle of the situation and tries to affect it, as opposed to observing it from a distance. It is a desire to be involved in things and some might describe that as an impulse towards intervention.

SB: As a Canadian filmmaker, what inspired you to tell a story set in the Philippines?

SD: My mother was born and raised on Leyte Island, which was basically ground zero for Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda is the Filipino name for it). At that time, it was the strongest storm ever recorded. When that devastation happened, I definitely felt very emotional about it. My cousin had lost her home in a different typhoon. They had all been relocated, not allowed to live on their land anymore. Seeing my cousin impacted that way really made me focus on what was happening in the Philippines. A friend and a mentor, Melina Laboucan-Massimo, had taught me that the meaning of responsibility is right there in the word. It is whatever your unique ability is to respond to something. It's not a burden or imposition. I've done stand-up comedy since I was a teenager. Filmmaking is another ability. I started to find ways to use those skills that I'd developed for many years and apply them in this context. I see it as an ancestral responsibility in a literal sense.

SB: Do you have insights on authentic story-telling that resists the white gaze?

SD: There are many layers to that answer. A Filipino writer, Merlinda Bobis taught a course at UBC titled, “How stories live in the diasporic body”. She taught an indigenous protocol that was specific to her region of the Philippines. It said, when a person passes on, all that we have left is their story to tell. For that reason, we must treat stories with the same respect and intention that we would treat the physical remains of our loved ones. When I'm dealing with stories that are not my own, set in the Philippines, I was taught to ask these questions: "Whose story is this to tell?", "What right do I have to tell it?", "What are my motivations that might influence how I am telling it?" and "How might the person whose story it is want it to be told in a different way?"

Having Arnel and Jaya (co-writers and protagonists of Asog) write with me, of course, makes navigating these questions much easier.

The final thing is–I am a bad Filipino. My mom spoke three Filipino dialects. I can't speak any of them. In the film, because people were not actors, we encouraged them to speak in whichever dialect they were most confident in. They understood the story we were trying to tell. There might be a pre-written joke in a scene but a lot of it often had someone's real experience, which did not require a script. Because I didn't know what they were saying until I heard it through a translator, my authorship of the film was surrendered to the process. There's more people involved than just me dictating everything that needs to be said.

film still from asog by seán devlin.

SB: While directing Asog, what did you hope to accomplish?

SD: This project is definitely not my own creation. Our storytelling process, though unique to the circumstances, has a very rich history. Augusto Boal’s theater of the oppressed was quite influential in how this film was made, especially the scenes with the folks in Sicogon Island who had their lands stolen. We urged them to tell their story, retell it, even add things that did not happen, so that leads to a different result in the real world. The ultimate goal was to tell a story that certainly has a lot of tragedy in it, but has a happy ending which exists in the real world, not just on screen.

Their land was stolen to build a resort and an airport. Since the film was finished, over 7 million CAD have been won in reparations. So far, they have built 434 new homes with that money. They are concrete, storm resistant homes. A bunch of them have solar power. It's amazing. But they still haven't received the paperwork for the land they were given, which is obviously crucial. That is why we are putting all this work into releasing the film in different countries one by one, to keep bringing people into the campaign to hold these corporations responsible for what they owe this community. But we are most of the way there. That's really exciting, considering where we were a few years ago.

SB: Do you have any advice to emerging independent filmmakers who might want to tell impactful stories with minimal resources?

SD: To begin with, ground yourself in your means. That way, you don't have to wait to raise money. Once you resign yourself to working with modest resources, you can make something that’s more unique, less concerned with making a big box office and more concerned with other things that might interest you, whether that be things you personally want to express, or sociopolitical issues you want to impact. Everything that's fascinating about how Asog is made tends to be a nightmare to a funder. Imagine my pitch, "I am going to this place, where I can't speak the language. No one in the movie has been on camera before. They are going to speak in different dialects and improvise.”

So much is possible, even with a small crew. We had five, sometimes six people, myself included. Ultimately people participate in small-budget projects like these because they believe in the purpose. But it requires a skill that is slightly different. It's organizing. If you embrace that style of working, a lot of other things become possible. You have power together, even if you are a small group.

Also, you should choose something that you really care about. My wife is the lead producer in the film. Together, she and I have put thousands of hours into this film. If fame and money motivates you but not something that moves you very deeply, it's hard to take a project to the finish line.

Shruthi (she/they) is a writer, zine-artist and cultural worker based in so-called New Westminster, on the unceded and unsurrendered land of the Halkomelem speaking peoples. She loves local theatre and is a regular writer for The Vancouver Arts Review. Distributing radical zines, creating cozy nooks for arts & crafts and soft check-ins with neurospicy peers are her love languages. With a diploma in creative writing from SFU’s The Writers Studio, their poems, short stories and collage-based zines delve into the nuances and wonders of cultural transplantation by drawing from feminist, fantasy writers and solarpunk aesthetics.